Purpose of this Blog

This website started as an outlet for students in Adriel M. Trott's Public Philosophy Senior Capstone course. It is now a website for sharing information about Wabash philosophy, studying philosophy in general and as an outlet for the Philosophy Club to engage.

Thursday, July 10, 2014

The Atlantic Monthly loves philosophers

What do philosophers do when they don't become professional philosophers? Reasons why you should major in philosophy? Read more in this Atlantic Monthly article.

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

Philosophy in the News (well, mostly the Atlantic Monthly)

The Atlantic Monthly has been talking about the growing number of philosophy majors for some time, as in this Atlantic Monthly article and more recently this Atlantic Monthly article (Wabash professors will be teaching both of the texts in that second article's picture, so yeah, we're current). But now they just can't stop talking about it as this article evidences.

Friday, March 7, 2014

Philosophy majors in the news: The Unexpected Ways Philosophy Majors are Changing the World of Business. Turns out, philosophy can change the world.

Monday, March 3, 2014

Wait... Seriously?

Thinking about writing and communicating via a written blog

provides some unique problems, but Jacques Derrida’s article titled "Signature Event Context" hopes to

modify the common conception of writing nonetheless. He explains that there is

a “distance", or "Differance" between the writer and the reader that can never be breached. Once

a writer has written something, the reader will have to come to some sort of

understanding on his or her own accord, which may not necessarily be what the

author intended.

Derrida elaborates on the distance between the author and the reader when he writes, “…a written sign carries

with it a force that breaks with its context... this breaking force is not an

accidental predicate but the very structure of the written text.” When an

author is in the midst of writing, much like I am at this very moment, the

author is in, “a certain ‘present’ of the inscription the presence of the

writer to what he has written…the wanting-to-say-what-he-means.” The “present

of the inscription”, for Derrida, is something like the context in which an

author’s work was originally produced. The meaning of the author’s writing,

however, is not determined by this context. When a person writes something, those words must have meaning to a reader regardless of original intent or the context in which it was written.

In

an attempt to re-word this idea a little more directly, Derrida suggests that

the original context and intention of an author does not have command over what

the author’s text actually means. This concept becomes even more interesting

when we think about how it impacts the process of interpreting another author’s work. Because

Derrida believes in an irreducible absence of an author's intention and attendance, the

reader or interpreter of a text is left to glean meaning from nothing but the text itself. The context in which a text was written or the

original intent of the author cannot be determined from reading someone’s work,

which leaves a reader with nothing but the written words that formulate a

specific, coherent work to determine meaning.

To

illustrate my point, one mode of communication comes to mind: satire. For

example, let’s look at a recent article published by The Onion regarding the first openly gay athlete in the NFL:

“Providing

further evidence of the hesitancy in professional sports to accept homosexual

athletes as equals, a new poll published Thursday revealed that more than 97

percent of NFL players are still not ready to date a gay teammate. "Throughout

the league there’s a lot of archaic attitudes toward homosexuality, and I’m

just not sure NFL players are comfortable enough to enter a monogamous

relationship with a gay teammate," said an anonymous player who felt that a

steady dating situation with a homosexual teammate wouldn’t be worth the

distractions in the locker room.” Full Onion Article

If we were to accept Derrida’s

explanation of writing, we quickly begin running the risk of positing a

inherently incorrect interpretation of this article as “true.” For Derrida, if I, as the

reader, acknowledge that this bit of an article has become separated from the

author’s original context and intentions, I am left to my own devices to glean

some significance from the words before me. I must use the system of symbols

and meanings found within the quote to determine a fair interpretation of the text.

So, what does The Onion article mean? Allow me to rehearse a false interpretation that Derrida’s concept of authorship would accept as true: It is a

news story concerning a major breakthrough in the NFL. Just as the rest of our

country, the National Football League is adjusting to an evolving and more

accepting world, but this change doesn’t come without growing pains. For

example, some players just don’t feel ready to start dating other men. Gay

athletes might be able to play professional sports without hiding their

sexuality, but the rest of the players still aren’t ready to embark on romantic relationships with their gay teammates.

For those unfamiliar with The Onion, the interpretation I just

provided is unequivocally misguided. The Onion, by nature, is sarcastic or

facetious; it is not meant to be taken seriously. Positing that this article is

an attempt to explain the unique dating pressures surrounding the first openly

gay NFL player is simply incorrect. In fact, the article’s purpose is much

different. Through humor, the Onion is attempting to mock the media firestorm

surrounding Michael Sam and his entering this year’s NFL draft. Networks like

ESPN seem to mention the fact that an openly gay man is playing football every

twenty minutes. They bring in current and former players and coaches to explain

how a gay player will affect an NFL team. It seems The Onion saw this constant focus on Michael Sam as an opportunity

to poke fun at the often mellow-dramatic sports media and the way this story has been covered.

It seems satire, in general, provides an interesting challenge to Derrida's concept, because satire relies on the manipulation of implied intention. The Onion writes poignant and funny articles because they are written in a way that makes them appear and sound earnest. In this way, The Onion's satire works because the implied intention stands in direct contrast to the author's sincere intention, which is to highlight the media's folly by pretending to take absurdity seriously. Lastly, it is important to note that this sarcasm is determined by the author of the text, not the reader: an audience can laugh at what appears to be serious because it is understood that, in fact, the author intended just the opposite.

According to Derrida, however, my

initial understanding of this article is justified. The reason I know the Onion

is meant to be taken as a joke is because the Onion does not hide their

intentions. Somebody who regularly reads The Onion is aware of these sarcastic

intentions, despite the fact that they are never explicitly written in the

text. This, however, means that Derrida would not be able to use a relation of symbols

strictly limited to this article to understand what it means. Derrida, after

rendering an attempt to understand the author’s intentions useless, allows for the possibility of justifying a falsehood. Furthermore, someone who subscribes to Derrida’s

outlook would not only run the risk of misreading this text, but it becomes almost impossible to prove how or why a literal interpretation demonstrates misunderstanding. There is no evidence

suggesting The Onion’s article is

meant not to be taken seriously within the given quote, yet the meaning of the

quote is determined, at least in part, by the author’s implicit intent.

Using a line of thinking that

hopefully resembles Russell’s correspondence theory (Stanford Encyclopedia Summary) , a re-focused summary of my argument looks

something like this: “The Onion's article is sarcastic” is a true interpretive statement

because it corresponds to the true fact that “ The Onion wrote a facetious article” (remembering that they write this way because they very much intend to). However, if I said, “the onion’s article is a literal and sincere news

story,” Derrida’s philosophy makes it impossible to have this statement

correspond to any true fact outside of the article itself. I cannot posit, “The Onion intends for their

news to be taken seriously” or that “ The Onion does not intend for the news to

be taken seriously” because an author’s intent no longer impacts the meaning

of the text. The inability for Derrida to fully account for the truth underlying either of these statements allows for the potential to justify false interpretations.

It seems the only way to understand the meaning of such a

satirical piece of writing is to understand that the author did not intend to

be taken seriously. In the case The Onion’s

brand of satire, ignoring the author’s intention is turning a blind eye to

the meaning of the text, a meaning that cannot be recovered as long as the reader remains ignorant of original intent.

The N-word

The NFL or National Football League has been under great scrutiny for their constant implementation of rules that are for the "safety" of the players. Many people have jokingly said that it's like a tough game of two-hand-touch. The league has lost a lot of respect for being the rough and tough game that it was back in the 1980's and early 1990's. With this being said, the NFL is at it again, implementing a rule that this time isn't for the players physical health, but presumably mental health this time.

The NFL is thinking of implementing a rule that would forbid any player on the field from using the N-word without consequence; consequence being a 15 yard penalty for the team that the player represents.

Michael Wilbon of ESPN has been against this rule from the time that it was brought up as being possible, to the point that it has become a reality. His argument against this rule is that he knows many people that use the N-word and isn't a derogatory term by any stretch, in fact it is a term used to refer to friend. Michael went above and beyond to prove his point that it isn't about the word as much as it's about "who uses it."

This concern is best brought up in the face of Derrida I believe. Because Derrida seems to believe that through the work of an author, no matter the author, the truth can be found if the author is no longer around. That the author isn't necessary for the correct meaning to found in the piece of work being studied. Therefore in this situation it is possible that Derrida would critique this rule because although we could posit arguments for what the meaning of the words are that a football player speaks to another, we wouldn't know that we have the correct meaning without knowing the meaning of author himself.

This problem will be a major sticking point in sports for years to come, I'm sure. But one thing I think is important to keep in mind when determining if author matters or not, is the fact that dissecting someone's words and words alone is a science. There is a specific meaning to each individual word and if we dissect meaning in this way than it must be a science. However the problem with this is the fact that satirical literature will never be understood when we try to find meaning via a scientific proof the way that the NFL is trying to do.

Sunday, March 2, 2014

Up in smoke...[Parental Discresion].

Disclaimer: This post contains content related to Marijuana and other paraphernalia as well as explicit lyrical content and a movie containing content that is rated by some organization with more morals than I as being for mature audiences only. You have to purchase the movie to watch it, so I am not responsible for your viewing anything other than the preview. Should the preview offend you, I guess I will care if Hinduism is right and I am reincarnated as a fruit fly in Hays Hall.....I probably still won't care...

Do you all remember the Cheech and Chong movies? Quite the comics back in their day. Recently, rappers Snoop Dogg (now Snoop Lion) and Wiz Khalifa starred in a movie called Mac and Devin go to High School. The movie can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, for a fee of course. Mac and Devin go to High School is a movie which is promoting, arguably, four things: marijuana acceptance, acceptance of the culture of the modern younger generations or at least a major sect of it, as well as unity, and it also might be critiquing the American Educational System.

These four constructs can, I am claiming, be best explained if we accept Foucault's analysis of the author in his work, What is an Author?. In this work, Foucault claims that the author is dead as we only refer to the author and do so in various and important ways and ultimately, as Michael Mancher puts it (sorry, it only gives the abstract when I try to link it),

This film falls under a couple of categories. First, the "stoner movie" category, the archetype for which might arguably be any of Cheech and Chong's films. This is not to say that this movie ought to be measured against any of Cheech and Chong's movies as I am sure that there are many stoner movie-connoisseurs that can find all of the finer tones of the classics that make the old better than the new. This is to say, however, that this movie is intended to be viewed in an altered state, namely, while under the influence of marijuana. Though I am in no way a legalist I do not condone illegal acts. Enough said. The second category that this movie falls under, and the more important one, is the "Snoop and Wiz" category. These two rappers are known for their less violent (especially now for Snoop) approach to hip-hop. Their lyrics focus less on the violent side of gangster rap and more on the creature-comforts, namely getting high and copulating. This movie focuses mainly on the former but still has some rather explicit inclusions of the latter. This is, arguably, very telling of a very significant sect of today's youth, good or bad -- take that as you may.

This film falls under a couple of categories. First, the "stoner movie" category, the archetype for which might arguably be any of Cheech and Chong's films. This is not to say that this movie ought to be measured against any of Cheech and Chong's movies as I am sure that there are many stoner movie-connoisseurs that can find all of the finer tones of the classics that make the old better than the new. This is to say, however, that this movie is intended to be viewed in an altered state, namely, while under the influence of marijuana. Though I am in no way a legalist I do not condone illegal acts. Enough said. The second category that this movie falls under, and the more important one, is the "Snoop and Wiz" category. These two rappers are known for their less violent (especially now for Snoop) approach to hip-hop. Their lyrics focus less on the violent side of gangster rap and more on the creature-comforts, namely getting high and copulating. This movie focuses mainly on the former but still has some rather explicit inclusions of the latter. This is, arguably, very telling of a very significant sect of today's youth, good or bad -- take that as you may.

As far as a standard of comparison is concerned, this movie can have two directions of comparison. One to Snoop's past lyrics and the other to Wiz's. As I have already mentioned, they like smoking weed and having sex. These themes are consistent across both of their portfolios in their raps as well as their cinema.

The third facet of this Foucaultic analysis of authorial intent is the reference to the actual characters themselves as authors. I think that it helps here to consider Snoop and Wiz more in terms of the characters that they play as well as their real-life selves. The characters that the two are playing are in high school. Spoiler alert, Mac (Snoop) is a repeat failure, held back academically for fifteen years or so and a daily stoner, enjoying the finer things in life which is the supposed reason he has yet to graduate. Devin (Wiz) plays the reigning valedictorian at N. Hale High School who is struggling to keep his spot at valedictorian and get his scholarship to Yale with his overbearing girlfriend. To make a long and very entertaining story short, the film depicts the wonderful life of being a kid in today's school system and does so by depicting said life in a high school centered around the consumption of cannabis.

Are Snoop and Wiz and the producers, themselves, making a claim about American education, or lack thereof? Whatever the case may be, two pop-culture icons have made a rather successful movie, and may have tried to provide a little insight into the phenomenon of American schooling which is seemingly lacking in terms of the claim of education. This movie pushes the themes of marijuana awareness and acceptance, draws attention to the culture of a large part of our modern-day youth, and speaks to the unity that can be had, even if it is mediated by a scheduled substance. The meaning of this film, again, take it as you will, can be, in my opinion, best understood by a careful inspection in the fashion of Michel Foucault's work What is an Author. Also, as a final point, I think more attention should be spent questioning what is acceptable as education. If what we are doing today is so off-putting that youth are turning to drugs instead of "education", which I am not claiming that marijuana is itself good or bad, but if weed is the magical ingredient, then perhaps we have cause for questioning.

Do you all remember the Cheech and Chong movies? Quite the comics back in their day. Recently, rappers Snoop Dogg (now Snoop Lion) and Wiz Khalifa starred in a movie called Mac and Devin go to High School. The movie can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, for a fee of course. Mac and Devin go to High School is a movie which is promoting, arguably, four things: marijuana acceptance, acceptance of the culture of the modern younger generations or at least a major sect of it, as well as unity, and it also might be critiquing the American Educational System.

These four constructs can, I am claiming, be best explained if we accept Foucault's analysis of the author in his work, What is an Author?. In this work, Foucault claims that the author is dead as we only refer to the author and do so in various and important ways and ultimately, as Michael Mancher puts it (sorry, it only gives the abstract when I try to link it),

"Foucault sees the author-function as one which reveals the convergence of a complex web of discursive practices. As these practices change or disappear and as new practices appear, the author-function will necessarily reflect those changes. Thus, the author-function can be described in sociohistorical terms as a practice or group of practices."Keeping these things in mind, the intention of this movie can be seen best, which is not to say that this movie's philosophies are the best, if we accept Foucault's analysis. The "practices that change or disappear" that Foucault talks about are the category that the works of the author fall under and are referred to by the name of the author, the author being a standard of comparison that other works are measured, and the actual person that the author is and that his/her text(s) (works) refer(s) to (Mancher, 1995).

This film falls under a couple of categories. First, the "stoner movie" category, the archetype for which might arguably be any of Cheech and Chong's films. This is not to say that this movie ought to be measured against any of Cheech and Chong's movies as I am sure that there are many stoner movie-connoisseurs that can find all of the finer tones of the classics that make the old better than the new. This is to say, however, that this movie is intended to be viewed in an altered state, namely, while under the influence of marijuana. Though I am in no way a legalist I do not condone illegal acts. Enough said. The second category that this movie falls under, and the more important one, is the "Snoop and Wiz" category. These two rappers are known for their less violent (especially now for Snoop) approach to hip-hop. Their lyrics focus less on the violent side of gangster rap and more on the creature-comforts, namely getting high and copulating. This movie focuses mainly on the former but still has some rather explicit inclusions of the latter. This is, arguably, very telling of a very significant sect of today's youth, good or bad -- take that as you may.

This film falls under a couple of categories. First, the "stoner movie" category, the archetype for which might arguably be any of Cheech and Chong's films. This is not to say that this movie ought to be measured against any of Cheech and Chong's movies as I am sure that there are many stoner movie-connoisseurs that can find all of the finer tones of the classics that make the old better than the new. This is to say, however, that this movie is intended to be viewed in an altered state, namely, while under the influence of marijuana. Though I am in no way a legalist I do not condone illegal acts. Enough said. The second category that this movie falls under, and the more important one, is the "Snoop and Wiz" category. These two rappers are known for their less violent (especially now for Snoop) approach to hip-hop. Their lyrics focus less on the violent side of gangster rap and more on the creature-comforts, namely getting high and copulating. This movie focuses mainly on the former but still has some rather explicit inclusions of the latter. This is, arguably, very telling of a very significant sect of today's youth, good or bad -- take that as you may.As far as a standard of comparison is concerned, this movie can have two directions of comparison. One to Snoop's past lyrics and the other to Wiz's. As I have already mentioned, they like smoking weed and having sex. These themes are consistent across both of their portfolios in their raps as well as their cinema.

The third facet of this Foucaultic analysis of authorial intent is the reference to the actual characters themselves as authors. I think that it helps here to consider Snoop and Wiz more in terms of the characters that they play as well as their real-life selves. The characters that the two are playing are in high school. Spoiler alert, Mac (Snoop) is a repeat failure, held back academically for fifteen years or so and a daily stoner, enjoying the finer things in life which is the supposed reason he has yet to graduate. Devin (Wiz) plays the reigning valedictorian at N. Hale High School who is struggling to keep his spot at valedictorian and get his scholarship to Yale with his overbearing girlfriend. To make a long and very entertaining story short, the film depicts the wonderful life of being a kid in today's school system and does so by depicting said life in a high school centered around the consumption of cannabis.

Are Snoop and Wiz and the producers, themselves, making a claim about American education, or lack thereof? Whatever the case may be, two pop-culture icons have made a rather successful movie, and may have tried to provide a little insight into the phenomenon of American schooling which is seemingly lacking in terms of the claim of education. This movie pushes the themes of marijuana awareness and acceptance, draws attention to the culture of a large part of our modern-day youth, and speaks to the unity that can be had, even if it is mediated by a scheduled substance. The meaning of this film, again, take it as you will, can be, in my opinion, best understood by a careful inspection in the fashion of Michel Foucault's work What is an Author. Also, as a final point, I think more attention should be spent questioning what is acceptable as education. If what we are doing today is so off-putting that youth are turning to drugs instead of "education", which I am not claiming that marijuana is itself good or bad, but if weed is the magical ingredient, then perhaps we have cause for questioning.

Bohemian Oversights

We're often convinced that compositions rich with imagery -- works of fiction, certain musical pieces, poetry, and so on -- possess deeper meanings than what we can glean from surface-level interaction with them. But who or what endows each composition with a deeper meaning? There are at least two potential solutions to this question (and perhaps they're just long-standing arguments that don't really get at any solutions at all): 1) The creator of the composition is the one who provides its deeper meaning. 2) The societal (dis)placement circulates the composition and thus provides its deeper meaning.

By societal (dis)placement, I mean two separate things. First, let's neglect the parenthetical "dis." When we turn our attention to these compositions, we can't help but think that there are a number of contextual or societal side issues that demand our focus in addition to the primary compositions in question. Things like time period of production, or whether the composition's advent was in reaction to something separate from it, or the political climate surrounding the composition's initial presence. The other meaning of (dis)placement I hope to make clear, the one for which "dis" is not optional, is the possibility that the composition might be ripped entirely out of the clutches of the author's initial intention and reformed by societal influences -- in this case, the composition's significance would be replaced.

Let's dive into these potential solutions with regard to a musical composition rather than the broader "compositions rich with imagery." We'll use some philosophical concepts too, but only as guides for insight. I am inspired by the words of our own Dr. Trott, who stated in a previous blogpost that it is better that we not enter into discourse with our standing beliefs and understanding of philosophical systems as weapons for justification, but rather that we be open to real conversation that doesn't rely on our particular biases.

-- "Sometimes I Wish I'd Never Been Born at All" --

A deeper meaning embedded in Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody"is claimed to exist. Not only do fans who obsess over the composition debate this deeper meaning, but the band itself asserts that there is one. But here's the catch: they won't disclose it.

So how do we reconcile these two issues? The first solution mentioned earlier, concerning authorial intention, doesn't seem completely adequate: we find hints of the second solution seeping in. Freddie Mercury, the creator, refused to explain the lyrical meaning, which shows us that Mercury probably had one in mind. But because it has been kept secret still by the living members of the band, societal (dis)placement has had to take over.

Jacques Derrida weighs in on this when he considers code in an essay entitled "Signature Event Context." His overarching claim is that in order for something to be considered writing, it must be able to function in the absence of both the writer and whom the writer addresses. For Derrida, codes can never be secret, because each coded message is capable of being deciphered, "iterable for a third party," and so capable of being decoded over and over again even if the writer and the intended recipient cease to exist.

Jacques Derrida weighs in on this when he considers code in an essay entitled "Signature Event Context." His overarching claim is that in order for something to be considered writing, it must be able to function in the absence of both the writer and whom the writer addresses. For Derrida, codes can never be secret, because each coded message is capable of being deciphered, "iterable for a third party," and so capable of being decoded over and over again even if the writer and the intended recipient cease to exist."Bohemian Rhapsody" stands as a code, then, and it seems that Derrida would say that, even if Queen's members all passed away, because there is an encoded meaning, we can still consider "Bohemian Rhapsody" a work of writing -- someday, somewhere, even if everybody who knew of Queen and their meaning-filled song had passed away, the coded contents, indeed the meaning, could be repeated.

But is that a satisfying answer? Derrida seems to suggest that writing necessitates absence, and not just metaphorical absence. Writing is divorced from the author the moment it is written; writing has no need for readers in order to be what it is, but it only needs to retain the possibility of being repeated, cited, whether on purpose or on accident.

Derrida's stance appears to align almost completely with the second of the two solutions above, that of societal (dis)placement, and even further than that, his seems to align with the second of the two interpretations of (dis)placement provided earlier -- if citation and repeatability determine that something is writing, then society is responsible for endowing a composition with meaning and pulling the textual offspring from the clutches of the parental author. Society is responsible for the divorce of text and author; it couldn't be any other way.

I wonder if it is enough that somebody might someday happen upon what Mercury meant by his lyrics. After all, if Queen keeps good on the promise (threat?), there will be no way to corroborate societal interpretation with authorial intention. Unless, of course, if in instances like this, when the composer refuses to disclose the meaning of a composition, that is the intention.

E. D. Hirsch, a scholar of a different mind than what we've seen in Derrida, argues in an essay entitled "Validity in Interpretation" that authorial intention ought not to be banished when the aim is understanding a text's meaning. He blames poets T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound for the onset of the era in which it became "sensible" to ignore the author -- but this can't be fair, can it? Perhaps Hirsch is partially right. Eliot and Pound may have claimed that, for their particular compositions, it would be better for their readers to be kept in the dark about their poems' meanings. Here again, just as we found in our analysis of Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody," it might very well be the case that the two poets intended for this darkness.

Musical, poetic, perhaps even fictional compositions do not receive their import from the existences of every other musical, poetic, or fictional composition. A stone foundation does not become made of sticks merely because the house atop the foundation is made of sticks. Every composition is not divorced from the meaning that its author imparted just because some composers have intended to keep their intentions hidden. Even when the intention is concealed, we cannot ignore authorial intention.

Writing doesn't exist if there is no writer, a fact inverted in the writing of Derrida, who claimed that writing necessitates its author's absence. And a foundation's nature doesn't change just because something else is stacked on top of it, a fact inverted in the analysis of Hirsch, who claimed that the plague of ignoring authorial intent could have been started by the intentions of a couple of poets.

E. D. Hirsch, a scholar of a different mind than what we've seen in Derrida, argues in an essay entitled "Validity in Interpretation" that authorial intention ought not to be banished when the aim is understanding a text's meaning. He blames poets T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound for the onset of the era in which it became "sensible" to ignore the author -- but this can't be fair, can it? Perhaps Hirsch is partially right. Eliot and Pound may have claimed that, for their particular compositions, it would be better for their readers to be kept in the dark about their poems' meanings. Here again, just as we found in our analysis of Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody," it might very well be the case that the two poets intended for this darkness.

Musical, poetic, perhaps even fictional compositions do not receive their import from the existences of every other musical, poetic, or fictional composition. A stone foundation does not become made of sticks merely because the house atop the foundation is made of sticks. Every composition is not divorced from the meaning that its author imparted just because some composers have intended to keep their intentions hidden. Even when the intention is concealed, we cannot ignore authorial intention.

Writing doesn't exist if there is no writer, a fact inverted in the writing of Derrida, who claimed that writing necessitates its author's absence. And a foundation's nature doesn't change just because something else is stacked on top of it, a fact inverted in the analysis of Hirsch, who claimed that the plague of ignoring authorial intent could have been started by the intentions of a couple of poets.

Sunday, February 23, 2014

The Self-Inoculating Insight of House of Cards

The Netflix series, "House of Cards," which is a remake of the British show by the same name, is in the second season. Since the whole season was available at once, critics and just about everyone else binged. While some critics (like those at Slate) recognized that the series is trashy, many loved it (Under the Radar, Star Tribune, Rottentomatoes) and social media blew up with accolades. What I find interesting is the way people think this show is profound, and the "the anti-hero turned villain"the best character on television.

I don't think it is. I think the second season is worse than the first, where there is an actual challenge to Frank Underwood's success. It isn't just that the second season (SPOILER ALERT) where Frank moves from being the Vice-President to the President in 13 episodes by destroying the President, is difficult to believe, but it gives us a false sense of watching the workings of power. We learn from Nietzsche that the powerful take pleasure in suffering and that we take pleasure in suffering because it gives us a feeling of power. I'm struck by how this show works then to vicariously make us feel powerful, while dulling our outrage in response to the abuse of power. In fact, I'm struck by the parallel that the effect of this show has to what one Plato scholar, Tom Davis, has called the self-inoculating insight that Socrates' interlocutors have over and over to prevent them from really examining themselves.

In Plato's Laches, Socrates is speaking with a number of Athenian generals about how to raise their sons. Socrates leads them to see that the question that needs to be examined is whether any one of them is an expert in the care of the soul, the knowledge that would be needed to raise their sons to have good souls. Socrates, as is his wont, denies that he has this knowledge, and encourages his Lysimachus, one of the generals to question Laches and Nicias, the other generals in order to see if they have this knowledge that would make them capable of caring for their souls. But before that investigation could happen, an investigation that would force them to confront their own lack of knowledge about what they claim to be good at, Nicias interrupts and tells Lysimachus how Socrates works: that "Socrates will not let him go before he has well and truly tested every last detail" (188a). Instead of submitting himself to this testing, Nicias discusses how the testing works and what it accomplishes. It isn't that Nicias is wrong here--he describes Socrates' elenchus well--but that what he performs is a way of using his insight to escape having to actually respond. I argue that this show accomplishes the same thing.

"House of Cards" allows us to act as if we have insight--power corrupts--but it protects us from having to respond and allows us to just wallow in the pleasure of a successful villain whom we may or may not be rooting for but are certainly captivated by. It allows us not to think about and respond to the power structures that make corruption in power possible in a way that would force us to have to consider what role we play in that structure and what we can do to change it. In this sense, I think "House of Cards," is very different from a show like, "The Wire."

David Simon's hit HBO show depicted a failed contest between cops and drug dealers where the losers were the cities and citizens. There was a fascination with the show because of its grim reality that left the viewer never satisfied and often frustrated. Drug plans that worked were cancelled because of "optics." The drive to statistics led to gross incompetence and the greater concern for closing cases than for justice. In the end (SPOILER ALERT) one of the main characters, a homicide detective, invents a serial killer in order to get the much needed funds to stop a drug kingpin. Nobody wins. No viewer feels innoculated. You keep watching because you think you are responsible to know. And with that knowledge to respond.

I don't think it is. I think the second season is worse than the first, where there is an actual challenge to Frank Underwood's success. It isn't just that the second season (SPOILER ALERT) where Frank moves from being the Vice-President to the President in 13 episodes by destroying the President, is difficult to believe, but it gives us a false sense of watching the workings of power. We learn from Nietzsche that the powerful take pleasure in suffering and that we take pleasure in suffering because it gives us a feeling of power. I'm struck by how this show works then to vicariously make us feel powerful, while dulling our outrage in response to the abuse of power. In fact, I'm struck by the parallel that the effect of this show has to what one Plato scholar, Tom Davis, has called the self-inoculating insight that Socrates' interlocutors have over and over to prevent them from really examining themselves.

In Plato's Laches, Socrates is speaking with a number of Athenian generals about how to raise their sons. Socrates leads them to see that the question that needs to be examined is whether any one of them is an expert in the care of the soul, the knowledge that would be needed to raise their sons to have good souls. Socrates, as is his wont, denies that he has this knowledge, and encourages his Lysimachus, one of the generals to question Laches and Nicias, the other generals in order to see if they have this knowledge that would make them capable of caring for their souls. But before that investigation could happen, an investigation that would force them to confront their own lack of knowledge about what they claim to be good at, Nicias interrupts and tells Lysimachus how Socrates works: that "Socrates will not let him go before he has well and truly tested every last detail" (188a). Instead of submitting himself to this testing, Nicias discusses how the testing works and what it accomplishes. It isn't that Nicias is wrong here--he describes Socrates' elenchus well--but that what he performs is a way of using his insight to escape having to actually respond. I argue that this show accomplishes the same thing.

"House of Cards" allows us to act as if we have insight--power corrupts--but it protects us from having to respond and allows us to just wallow in the pleasure of a successful villain whom we may or may not be rooting for but are certainly captivated by. It allows us not to think about and respond to the power structures that make corruption in power possible in a way that would force us to have to consider what role we play in that structure and what we can do to change it. In this sense, I think "House of Cards," is very different from a show like, "The Wire."

David Simon's hit HBO show depicted a failed contest between cops and drug dealers where the losers were the cities and citizens. There was a fascination with the show because of its grim reality that left the viewer never satisfied and often frustrated. Drug plans that worked were cancelled because of "optics." The drive to statistics led to gross incompetence and the greater concern for closing cases than for justice. In the end (SPOILER ALERT) one of the main characters, a homicide detective, invents a serial killer in order to get the much needed funds to stop a drug kingpin. Nobody wins. No viewer feels innoculated. You keep watching because you think you are responsible to know. And with that knowledge to respond.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

The Walking Dead

In a world in which we have not encountered the actuality of "zombies," outside of someone drowning themselves figuratively in bath salts, they have become an increasingly hot topic in the pop culture realm.

The Walking Dead sets up a very nice Platonic setting in which the main character, Rick Grimes, is played out as the philosopher-king, and Shane Walsh is playing the part of Thrasymachus.

In Plato's Republic he battles Thrasymachus to a point of physicality in that it isn't as much about Thrasymachus fighting with Socrate's argument as it is Socrates himself. This plays out very nicely in Shane's battle with Rick. Rick is the thinking and decision making mind for the group of survivors while Shane is the act now, decide later member of the group. Joseph Campbell's article goes more in-depth with this notion of the philosopher-king and I believe it to be a great insight for myself and possibly others who may have lost interest.

It would seem to me that for those of us who have found ourselves just watching the show in passing and not really becoming a part of it, or even becoming interested in it, it's because of the chaos and fighting that it has lost it's spunk. Obviously a show with zombies is going to include fighting when the zombie's character eats people. Fighting in the sense of little spats amongst the group that last for three episodes is the type of fighting that has become uninteresting and mind-numbing. The chaos falls in line with this notion of fighting in-so-far-as the philosopher-king does more acting out and less thinking now. Rick has to constantly defend and argue with the group about every single little decision that he makes, whether it's for himself, another person, or the entire group. He is no longer truly thinking and being the leader as he is the guy under the sheriffs cap waiting to be replaced by his son.

As a society I believe that we (I don't speak for everyone) have began to love the idea of acting and doing the reminiscing or thinking afterwards as opposed to the other way around. The Walking Dead has taken up this very mindset in my opinion and therefore has lost my interest as a show that I will cancel plans to make sure I see. I'm not arguing that Plato's Republic is what keeps someone interested in a show, but it's possible that a more thought-based society would be worth giving consideration to.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

Existentialism in the Music

Reaching the end of my adventure through undergraduate study I have come to only have one regret. I do not even know if I call it a regret as the construct has nonetheless been a significant influence on my life. The regret, at long last, if it is even regret at all, is that I entered college after Dave Matthews swept the college scene when he and his band first began touring in the 90s. But that I missed their rise to fame is not the source of my fascination with the band. The band's philosophy is.

I discovered the Dave Matthews Band when I was somewhereabouts halfway through high school, but I only listened to this band because they had a bomb saxophone player, the late LeRoi Moore, and I had the Recently EP album, which was the first time I ever remember having an idol. I am a saxophone player. My whole family is of the musical sort, so why it is that I am trying to fool myself that I am an academic type I haven’t the slightest. I digress. Hearing the way that this band played really resonated with me, especially that I had never heard anything like this music, this jam-solo style, ever before in my life. It was not until I came to college, in my freshman year specifically, that I began to absorb and try to digest the lyrics that Dave let loose amidst the band’s melodies. It was at about that same time that I discovered Jean-Paul Sartre and the rest of the existentialist cohort while taking an intro Philosophy class. Really, Jean-Paul Sartre is the reason why I chose Philosophy as one of my majors. What does this have to do with Dave? Existentialism appealed very much to me. Especially since at that time I was amidst a very significant transitional phase in my life, the things that Dave spoke about echoed very much the same sense of responsibility and unity that existentialism focuses on. The Dave Matthews Band, seemed and still do to me like an existentialist band.

In an article written by Chris Schmarr on Dave Matthews' philosophy as evidenced by his history and lyrics, his interviews and what folks have come to call "Dave speak", he makes constant reference to things that make us all human, and Schmarr is keen to note many of the aspects of Dave's performances, as well as facets of his biography that resemble very closely themes in existential philosophy. A passage from the article by Chris Schmarr that I think best captures the theme of The Dave Matthews Band's philosophy is this:

Friedman, H. S. & Schustack, M. W. (2009). Personality: Classic theories and modern research (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. As odd as it may seem, I think that in the Dave Speak video, the decision on how best to poop in the ocean is a great example of personal responsibility and is made even better with the reference to the notion that we pollute the oceans terribly with our waste as a nation or society, but the one waste that is natural to an ocean, one that might actually be good for it, our individual pooping in an immense body of water, is something that we do not generally do for the construct of a social norm.

What made things very real for me was when I first heard the song, “Typical Situation” and Dave describes various things about nature and in our human world, things that I had taken for granted as existing. Things that might not seem to have much bearing on the meaning of our existence. He juxtaposes these things with the social construct of socially keeping in line for fear of reprimand. The idea of social conformity, for me, was and still is very troublesome. I had been confronted with it while pledging a fraternity, which I have to say, in my opinion, is about the most useless process as it stands, but that is a topic for a vastly different blog. Conforming is not something that I do unless I have very good justifications for doing so. This practice causes me problems socially, but it keeps me satisfied.

The song goes a little something like this: "Why are you different? Why are you that way? If you don't get in line we'll lock you away." For me this can be taken as the one fellow standing out of line, not in line with the rules, against the conformity of all the human companions standing in line, following the rules. Dave also says in that song, "Everybody's different. Everybody's free. Keep the big door open -- everyone will come around." If one takes those two lines along with another and it follows this way: "It's a typical situation in these typical times. Too many choices. We can't do a thing about it; too many choices."

I suppose the overarching theme here between existentialism and DMB is that both are concerned with the choices that we are faced with in our existence. Numerous, overwhelming. So many choices. And another thing, if the final line, "It all comes down to nothing," has any bearing on this connection, then it is parallel to the despair one feels when one has the foundation of their identity stripped from themselves. Perhaps it is the center of nihilist philosophy, where there is no meaning and no point in rules and institutions. This is the nothingness that we find ourselves in, the absurdity that is the world through the eyes of an existentialist. The existentialists believe that there is no meaning in the world apart from what we assign to the world. This reduces humans apart from their institutions and social groups, reduces them down to individuals, as Kierkegaard would have it, that are tasked with living life defined by themselves and understood on their own terms.

But all this loneliness is not where it all stops. We don't just try to annihilate it all. It is not as Ivan Karamazov would say, that everything is permissible in the absence of God.

Sartre and, for all intensive purposes, Dave are both flavors of atheists. Sartre is a hypothetical atheist and Dave is just Dave (its a long interview, but I think that it is well worth it. If you wish not to listen to it all, he says that if God is even out there, there is not conceivable reason that God would give a damn about a little human). Responsibility comes full circle when existentialists claim that the value of a person is not given until they are dead. We are the sum of our actions. And for Dave, much of his concern comes from his existential angst toward the state of the humanity and the world. He is deeply troubled by the things that we are doing to each other and to our planet. Songs like Don't Drink the Water or Eh Hee (or Eh Hee for those of you that like the live stuff) where there is a strong urgency towards guilt and responsibility and the recognition of these things, one can see the concern Dave has for how we treat each other and how we act as humans. The Dreaming Tree or Gaucho one can see the concern for our actions on how we treat the planet. He is genuinely concerned with loving our fellow humans, on the grounds that we have nothing but ourselves. We owe it to each other and our children after us to think about how we treat each other and the consequences of our decisions.

I guess that the greatest thing that I have come to take away from my melting Existentialism and the Dave Matthews Band together is that I am just as screwed as everyone else. And that we are all in this together, God or not. I have suffered my own trials in my life and almost every time I had help from another person or persons along the way. It would be a sin for me not to help a person in need. That is the most important part of being human, aside from reproducing. Loving, and it’s the part that I think is too often forgone.

I discovered the Dave Matthews Band when I was somewhereabouts halfway through high school, but I only listened to this band because they had a bomb saxophone player, the late LeRoi Moore, and I had the Recently EP album, which was the first time I ever remember having an idol. I am a saxophone player. My whole family is of the musical sort, so why it is that I am trying to fool myself that I am an academic type I haven’t the slightest. I digress. Hearing the way that this band played really resonated with me, especially that I had never heard anything like this music, this jam-solo style, ever before in my life. It was not until I came to college, in my freshman year specifically, that I began to absorb and try to digest the lyrics that Dave let loose amidst the band’s melodies. It was at about that same time that I discovered Jean-Paul Sartre and the rest of the existentialist cohort while taking an intro Philosophy class. Really, Jean-Paul Sartre is the reason why I chose Philosophy as one of my majors. What does this have to do with Dave? Existentialism appealed very much to me. Especially since at that time I was amidst a very significant transitional phase in my life, the things that Dave spoke about echoed very much the same sense of responsibility and unity that existentialism focuses on. The Dave Matthews Band, seemed and still do to me like an existentialist band.

In an article written by Chris Schmarr on Dave Matthews' philosophy as evidenced by his history and lyrics, his interviews and what folks have come to call "Dave speak", he makes constant reference to things that make us all human, and Schmarr is keen to note many of the aspects of Dave's performances, as well as facets of his biography that resemble very closely themes in existential philosophy. A passage from the article by Chris Schmarr that I think best captures the theme of The Dave Matthews Band's philosophy is this:

Where Schmarr cites Friedman:At one point or another in our lives we begin to question our self-worth and purpose in life. Why are we here? Existentialism is described as an area of philosophy that is concerned with the meaning of human existence (Friedman, 2009, p. 294). Dave Matthews struggles with this issue on a constant basis and it can be seen in his lyrics. Existential philosophers place the responsibility of personality squarely on the individual. How an individual deals with love, ethics, anxiety, triumph, and death is completely up to that individual (Friedman, 2009, p. 320).

Friedman, H. S. & Schustack, M. W. (2009). Personality: Classic theories and modern research (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. As odd as it may seem, I think that in the Dave Speak video, the decision on how best to poop in the ocean is a great example of personal responsibility and is made even better with the reference to the notion that we pollute the oceans terribly with our waste as a nation or society, but the one waste that is natural to an ocean, one that might actually be good for it, our individual pooping in an immense body of water, is something that we do not generally do for the construct of a social norm.

What made things very real for me was when I first heard the song, “Typical Situation” and Dave describes various things about nature and in our human world, things that I had taken for granted as existing. Things that might not seem to have much bearing on the meaning of our existence. He juxtaposes these things with the social construct of socially keeping in line for fear of reprimand. The idea of social conformity, for me, was and still is very troublesome. I had been confronted with it while pledging a fraternity, which I have to say, in my opinion, is about the most useless process as it stands, but that is a topic for a vastly different blog. Conforming is not something that I do unless I have very good justifications for doing so. This practice causes me problems socially, but it keeps me satisfied.

The song goes a little something like this: "Why are you different? Why are you that way? If you don't get in line we'll lock you away." For me this can be taken as the one fellow standing out of line, not in line with the rules, against the conformity of all the human companions standing in line, following the rules. Dave also says in that song, "Everybody's different. Everybody's free. Keep the big door open -- everyone will come around." If one takes those two lines along with another and it follows this way: "It's a typical situation in these typical times. Too many choices. We can't do a thing about it; too many choices."

I suppose the overarching theme here between existentialism and DMB is that both are concerned with the choices that we are faced with in our existence. Numerous, overwhelming. So many choices. And another thing, if the final line, "It all comes down to nothing," has any bearing on this connection, then it is parallel to the despair one feels when one has the foundation of their identity stripped from themselves. Perhaps it is the center of nihilist philosophy, where there is no meaning and no point in rules and institutions. This is the nothingness that we find ourselves in, the absurdity that is the world through the eyes of an existentialist. The existentialists believe that there is no meaning in the world apart from what we assign to the world. This reduces humans apart from their institutions and social groups, reduces them down to individuals, as Kierkegaard would have it, that are tasked with living life defined by themselves and understood on their own terms.

But all this loneliness is not where it all stops. We don't just try to annihilate it all. It is not as Ivan Karamazov would say, that everything is permissible in the absence of God.

Sartre and, for all intensive purposes, Dave are both flavors of atheists. Sartre is a hypothetical atheist and Dave is just Dave (its a long interview, but I think that it is well worth it. If you wish not to listen to it all, he says that if God is even out there, there is not conceivable reason that God would give a damn about a little human). Responsibility comes full circle when existentialists claim that the value of a person is not given until they are dead. We are the sum of our actions. And for Dave, much of his concern comes from his existential angst toward the state of the humanity and the world. He is deeply troubled by the things that we are doing to each other and to our planet. Songs like Don't Drink the Water or Eh Hee (or Eh Hee for those of you that like the live stuff) where there is a strong urgency towards guilt and responsibility and the recognition of these things, one can see the concern Dave has for how we treat each other and how we act as humans. The Dreaming Tree or Gaucho one can see the concern for our actions on how we treat the planet. He is genuinely concerned with loving our fellow humans, on the grounds that we have nothing but ourselves. We owe it to each other and our children after us to think about how we treat each other and the consequences of our decisions.

I guess that the greatest thing that I have come to take away from my melting Existentialism and the Dave Matthews Band together is that I am just as screwed as everyone else. And that we are all in this together, God or not. I have suffered my own trials in my life and almost every time I had help from another person or persons along the way. It would be a sin for me not to help a person in need. That is the most important part of being human, aside from reproducing. Loving, and it’s the part that I think is too often forgone.

Dirty Wars and Socrates

Dirty Wars, a

documentary made by director Richard Rowley and journalist Jeremy Scahill, has

been nominated for best documentary in 2014, but it should turn heads for more

reasons than mere critical acclaim. Dirty

Wars follows Scahill as he travels the world following the exploits of the

United States military. During his investigative work, Scahilll comes across

one of the most secretive and powerful military units in the U.S.: Joint

Special Operations Command, or JSOC.

JSOC, as the documentary explains, is the only military unit that the President can contact directly and is scarcely mentioned in any official military reports. As the film unfolds, Schahill continues to discover more and more unsettling truths surrounding JSOC, including the killing of a seemingly innocent family. Possibly the biggest problem Scahill uncovers, however, is the fact that U.S. forces have been carrying out planned attacks in countries we are not at war with: “As Scahill digs deeper into the activities of JSOC, he is pulled into a world of covert operations unknown to the public and carried out across the globe by men who do not exist on paper and will never appear before Congress. In military jargon, JSOC teams ‘find, fix, and finish’ their targets, who are selected through a secret process. No target is off limits for the kill list… (official website ).” In other words, Dirty Wars provides sturdy evidence that suggests the United States’ war on terror has reached far beyond countries like Afghanistan.

The

government, including both President Bush and Obama, has used JSOC increasingly

over the years, but the secrecy surrounding this outfit makes it hard to

understand completely. Both Scahill and the audience are left to assume that

our government is in the process of using force and violence to eliminate whomever

our military deems as a threat, regardless of whether or not we have declared

war.

The

political issues surrounding Dirty Wars might

seem obvious, but I think America’s recent military trends have interesting

philosophical implications as well. In Plato’s

Republic, Socrates outlines different forms of government and explains

various pitfalls associated with each. With regard to democracy, Socrates seems

to caution against the exact thing our Scahill discovers in Dirty Wars. Socrates explains the motive

of a democratic leader by explaining that, “ …when he is reconciled with some

of his enemies outside and has destroyed the other, and there is rest from

concern with them, as his first step he is always setting some war in motion…(Bloom,

566e).”

Scahill

is afraid that the war on terror has become a war without end, but why would a

government be interested in constantly being involved in war? Socrates suggests

that war can be used as a tool for power. If there is war, then the people of a

democracy will need a leader to protect them from a perceived threat. Furthermore, as Socrates explains, war

costs money, and people with less money are more inclined to stick to their

“daily business”, allow people in power to do as they wish.

It

seems that Socrates’ wisdom may apply to the discoveries in Dirty Wars, but it probably isn’t fair

to assume American presidents are acting in such a sinister manner. But,

luckily for us, Socrates has plenty of wisdom to share. Just as Scahill

suggests in his documentary, Socrates explains that such constant war efforts

will eventually harm the health of the democracy as a whole.

Once

again in reference to a democratic leader and people that disagree with him,

Socrates states, “ Then the tyrant must gradually do away with all of them, if

he’s going to rule, until he has left neither friend nor enemy of any worth

whatsoever (567b).” As a democracy continues to go to war, the government and military

will get stronger out of necessity. As war gives power to the government, the

government continues to try and retain that power. More “enemies” are

discovered, and those “enemies” must be eliminated by any means necessary,

because the government’s fate depends on it. For Socrates, war in a democracy

will eventually become something like a self-fulfilling prophecy. A government

grows powerful from war and goes to war to remain powerful.

The problem? The people in charge

of eliminating threats are the same people in charge of determining threats.

War creates a need to consolidate power to increase efficiency, but it does

very little to make sure that power is properly monitored. An “enemy” of the

state can now be defined however the state sees fit. The goal of the democratic

government becomes remaining powerful, and the citizens suffer as a result.

What was once a government designed to preserve freedom devolves into something

that takes freedom away.

As Dirty Wars illustrates, an “enemy” of America can be an American

citizen, and the U.S. military is not afraid to eliminate such threats through

assassination. Anwar al-Awlaki. An American citizen, and his 16 year-old son,

also an American citizen, were killed by an American drone attack in Yemen on

September 30th, 2011( full article ). Al-Awlaki was affiliated with al Qaeda, but he

was killed without going to court, which is something American citizens are

constitutionally guaranteed. Even more shocking was the death of his son. The

16 year-old American citizen’s crime? Being the son of a wanted man. This case

is both extreme and rare, but they are sobering nonetheless.

All of these things lead us to one

question: is America following the very errant path Socrates describes in The Republic? We have been at war for over ten years and spent countless dollars. We have increased surveillance at the

price of personal freedom, and we have begun roaming the world in an effort to

kill all potential adversaries, including one of our own citizens. Socrates

warns against all of these thousands of years ago, yet they happen

nevertheless.

Whether or not America has reached

a point of serious concern is a debate I hope continues, but one thing is for

sure: we have been warned.

Cartoon Ethics and Presumption's Ugly Face

Sometimes it's interesting to cut back on philosophical pretension and talk about something that everybody has the chance to interact with and, more than that, to enjoy. Wiley-Blackwell lists 42 books in the Philosophy and... series, collections of authors and their articles employing philosophical lenses upon trending topics. The series gets mixed reviews, and John Shelton Lawrence addresses the issue of this popularizing trend over at Philosophy Now. He poses a few questions:

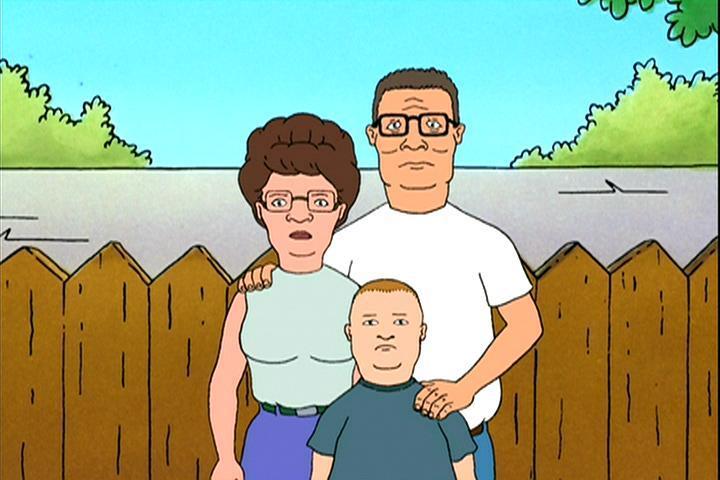

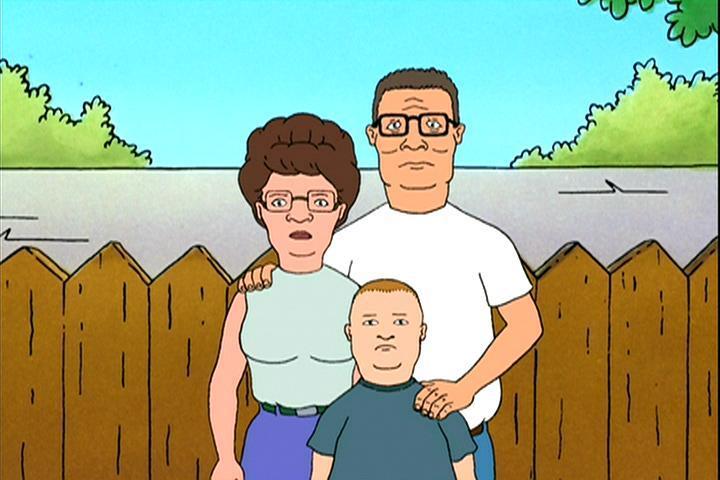

Last summer I decided to fill my few free hours between shifts at the gas station with episodes of Mike Judge's animated sitcom, King of the Hill. Proof of my interest in the series can be corroborated easily: check my last post--I use the character, Dale Gribble, as an example of the modern conception of a conspiracy theorist. The sitcom aired regularly for about twelve years and occupied a spot in Sunday night's primetime lineup. It was popular; actress Brittany Murphy voiced the character of Luanne Platter; it was on in a time-slot very close to the Simpsons. Kathleen Tuck, professor at Boise State University, described her summer time classes that connected pop culture and philosophy, and one source she drew from was the very same King of the Hill.

Last summer I decided to fill my few free hours between shifts at the gas station with episodes of Mike Judge's animated sitcom, King of the Hill. Proof of my interest in the series can be corroborated easily: check my last post--I use the character, Dale Gribble, as an example of the modern conception of a conspiracy theorist. The sitcom aired regularly for about twelve years and occupied a spot in Sunday night's primetime lineup. It was popular; actress Brittany Murphy voiced the character of Luanne Platter; it was on in a time-slot very close to the Simpsons. Kathleen Tuck, professor at Boise State University, described her summer time classes that connected pop culture and philosophy, and one source she drew from was the very same King of the Hill.

"Is this approach good for spreading philosophical awareness? Is it pandering to popularity, or progressive pedagogy that has finally realized where it must go to connect with student minds and hearts? Has philosophy sold its critical soul to entertainment franchises to recover student attentiveness?"

I want to claim that a philosopher ought to interact with social reality; could it be that we say that the philosopher dwells in an Ivory Tower because he refuses to engage with his immediate context too often? As a result and on the flipside, do those who are not philosophers ignore philosophy because the philosopher neglects to discuss things that exist outside of the academy? I think that these are worthy questions to ask, but in the meantime, I'm going to take the risk that philosophers should engage with social reality and trending topics sometimes.

Last summer I decided to fill my few free hours between shifts at the gas station with episodes of Mike Judge's animated sitcom, King of the Hill. Proof of my interest in the series can be corroborated easily: check my last post--I use the character, Dale Gribble, as an example of the modern conception of a conspiracy theorist. The sitcom aired regularly for about twelve years and occupied a spot in Sunday night's primetime lineup. It was popular; actress Brittany Murphy voiced the character of Luanne Platter; it was on in a time-slot very close to the Simpsons. Kathleen Tuck, professor at Boise State University, described her summer time classes that connected pop culture and philosophy, and one source she drew from was the very same King of the Hill.

Last summer I decided to fill my few free hours between shifts at the gas station with episodes of Mike Judge's animated sitcom, King of the Hill. Proof of my interest in the series can be corroborated easily: check my last post--I use the character, Dale Gribble, as an example of the modern conception of a conspiracy theorist. The sitcom aired regularly for about twelve years and occupied a spot in Sunday night's primetime lineup. It was popular; actress Brittany Murphy voiced the character of Luanne Platter; it was on in a time-slot very close to the Simpsons. Kathleen Tuck, professor at Boise State University, described her summer time classes that connected pop culture and philosophy, and one source she drew from was the very same King of the Hill.

But now for the insight. I noticed something about the show's structure after running a marathon through the long list of episodes. If the specific episode's plot focused around a single character, the presentation of other characters was altered accordingly. When the patriarch of the Hill household, Hank, held most significance for the plot of the episode, his wife, Peggy, would appear dull or, at the very least, uninterested in Hank's conundra. Alternatively, if the plot of the episode concerned Peggy Hill's character the most, Hank would appear as a bumbling idiot with concerns that shouldn't be concerns.

Perhaps I'm reading too much into this, and perhaps it might not have been Mike Judge's conscious intention to form the rest of the characters in an episode around the mindset of the central character, but it appears to demonstrate a subtle, ethical point. Here we have a series about a fictional family that takes advantage of the average, white, Texan stereotype. But layered beneath the dilemmas in the story lines, the humor in the generalizations, and the entertainment value that depends sometimes on cartoonish excess, we can find a significant truth about the nature of human interaction.

Perhaps I'm reading too much into this, and perhaps it might not have been Mike Judge's conscious intention to form the rest of the characters in an episode around the mindset of the central character, but it appears to demonstrate a subtle, ethical point. Here we have a series about a fictional family that takes advantage of the average, white, Texan stereotype. But layered beneath the dilemmas in the story lines, the humor in the generalizations, and the entertainment value that depends sometimes on cartoonish excess, we can find a significant truth about the nature of human interaction.

Both Hank and Peggy possess different lenses and each is probably ignorant of the opinions the other holds about them. The animated world literally seems to form itself around the central character of each episode. The ethical lesson is one of avoiding presumption. There's nothing worse than having someone believe or say that you're something or someone you're not. Misidentification hurts, especially when the one who isn't identifying correctly neglects to consult the object of identification.

The task before anyone hoping to intimately or purely understand God, a lover, a friend, or even a television series, is a laborious one that seems unsurmountable. But Peggy and Hank still live together, feel affection for one another; they bridge the gaps with something less impending than an inability to truly communicate and understand their respective worlds. Presumption thrives, of course, but we can stifle it back little by little, and we must, if we hope to make proper sense out of the beings we interact with.

Friday, February 7, 2014

It is of great argument as to whether women are being paid fairly in comparison to their male counterparts. A study completed in 2012 found that the median yearly earnings for full-time male employees was $49,398. However, for women it was found that the median was $37,791. This $11,000+ difference isn't something to scoff at. Figuring out how to fix this problem, if it is one, is of greater importance. After analyzing many statistics, it is hard to argue that there isn't a discrepancy in pay for men as opposed to women. However, let's entertain the thought of it not being about women being less fortunate, in pay, and instead happiness being lost.

Flipping an argument on it's head and completely undermining it should be met with hesitation but it will become clear as to why this shouldn't be such a surprise. If we take a look at what drives a human being, we may have a better understanding why it's possible that money isn't the root to all happiness. In fact, it may be possible that happiness is more important than money after all. Why would be arguing the amount of money one sex makes over another, if it isn't at the end of the day about the happiness of the individual?

A study done in 2010 found that happiness in the workforce, was at 30%. 30% of all full-time employees in the workforce were happy about their position and their life in general. If 30% are happy, then that leaves 70% that are obviously not happy/blah with the direction or landscape of their life/job. But making a median of $11,000 more than women per year; how can one be unhappy? It may be as simple as the fact that money doesn't buy happiness.

The stress put on dollar signs, is being unfairly sought after as the ultimate goal in life. We understand that the money differential between men and women is obvious and can be understood as being unfair in the sense that each person, based on sex, isn't making the same amount on average. However, if we were to fix this symptom, would we truly fix anything at all, or would we just be running further from the problem? The problem being that happiness is what we truly long for, and if we want fairness in the workforce, we don't want it for "fairness" in and of itself, we want it so that we are all happy and no one is felt cast off. 30% of all full-time employees aren't happy now and some of them are making more money than the average. What does this tell us about what we are arguing about? Is it possible we are addressing an issue that is but a symptom of the greater illness; unfound happiness?

We must embrace the discrepancies and understand that it isn't about the dollar signs put behind ones name but the amount of non-quantitative data that is found within one's life. It cannot be the fact that wealth makes someone happy who hasn't had the chance to earn it. The reason for this is because they wouldn't know what it is like until they had accomplished it, and therefore wouldn't know the happiness that could be gleaned from their monetary wealth. We assume that more money will make us happy but since we don't know, how do we decide that it will?

We only have an argument over something that we think will cause a difference in the lives of individuals in a positive manner. If this is the case than we are to assume that more money and more equal portions of money will equate to happiness within men and women. But then we are given a statistic that shows 70% of all full-time employees are either blah or hate their current job. But yet we want to pursue more money and equality in the thing that is causing over half of those involved to not be happy. Let us decide if happiness is what we truly want, or is it wealth. In this argument, it cannot be both. For if it is wealth than we have a larger problem on our hands, and that is, why do seek justice, laws, accountability, etc. if not for the happiness of each individual? And if it is happiness, than why pursue something that over half of those involved already dislike, and better yet, something that we don't truly know will make us happy?

What good do we desire?

Last year, with the firing of the Philosopher, McGinn, for his

grossly sexist acts and outright slap in the face remarks of his defense, many

feminist bloggers took to the web with this call to action to reconsider the

state of equality in the professional world, especially in the field of

philosophy where the numbers of female faculty there are floundering as

compared to other fields and professions.

In the midst of all this talk about equality and calling for a change in

the sad statistics that are yielded in my beloved field of study I heard

echoing somewhere in the distance something that Plato had illustrated to me

once in his Republic. In the midst of

all that noise, valuable as it all may have been, I asked myself, “What good

are we desiring?” If what we desire we

perceive to be the good, then why is it that there is such a terribly steep

ratio of men to women in philosophy.

I am not talking about the “good intentions” of feminist or

other civil rights groups here. What I

am aiming at is the more existential claim of where we are as a society with

respect to the lack of diverse philosophy faculty. And I hope that I can

adequately lead to a discussion of how we might or even ought to approach the

various possible causes of the gendered cliff.

I make a point about our existential well-being because I

think it is an interesting avenue to consider the idea that if our society, at

least here in America, were to be judged today its final judgment, what would

we have to say for ourselves? In a field

that is the breeding grounds for social movement, advancement, and propagation

of civil rights, how is it that this field is in possession of so little

diversity. Assuming that Heidegger was

on to something about making use of one’s available possibilities, would it not

seem beneficial to have the greatest array of equipment made available to

oneself, equipment in the form of the perspectives that our educators bring to

the academic table, making those perspectives available to us. I am not one to take sides in feminist

battles, really in any battles for that matter mainly on the grounds that there

are too many opinions flying around, more than I care to keep track of. But this is a matter not only of equality but

also of the potential for greater knowledge and I can see a possible avenue for

philosophy to rekindle its old flame, restore itself to its former grandeur in

the public eye if it is made more readily available to more people. Back to the existential question. How would we look under an existential